Walter Gropius

wp:heading {"textAlign": "center"} An indelible mark on 20th century modern architecture An indelible mark on 20th century modern architecture An indelible mark on 20th century modern...

Read our other blogs too

Whoppah explores: Eames Lounge Chair

The Eames Lounge Chair is undoubtedly one of the most popular lounge chairs ever made. The iconic chair was released by The Herman Miller Company in 1956 and is here to stay. Do you dream of such a beautiful copy? We share 5 facts about this legendary lounge chair and we spoke to Aksel, Eames connoisseur and trader, about the differences between the vintage and recent models of this chair.

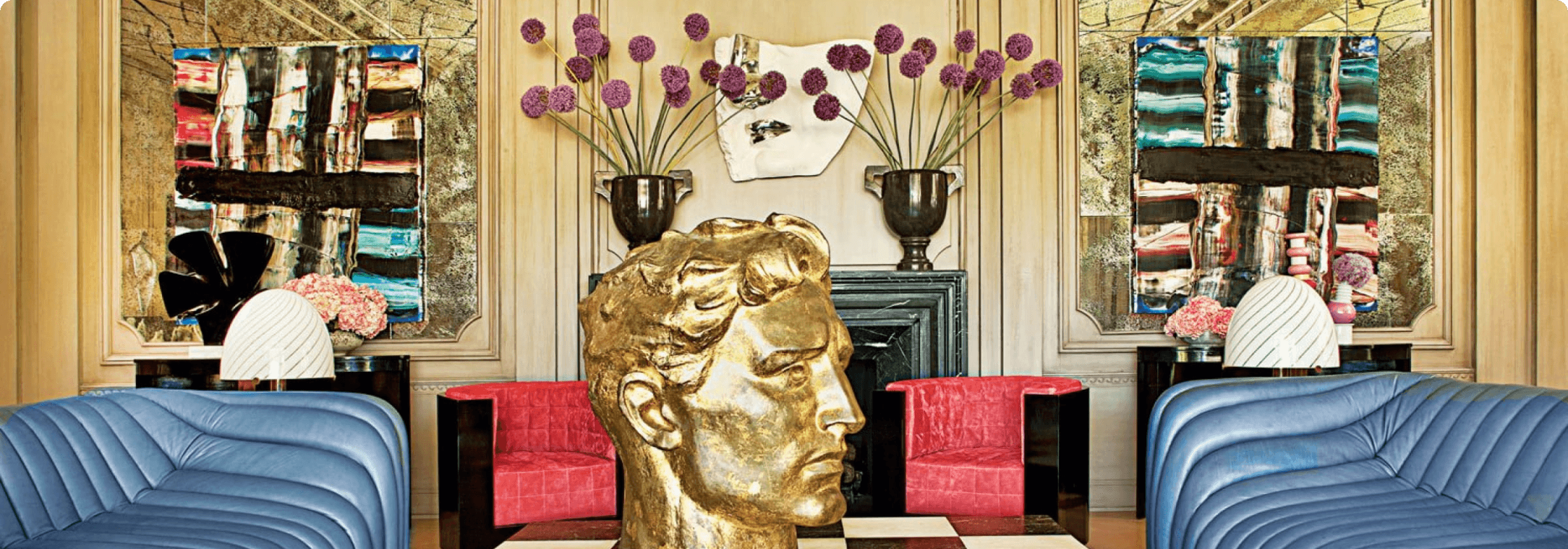

At home with Michael

Next up in our home visit series – where we come to your home to get to know you better, discover your style, and learn more about your relationship with secondhand and design – is Michael (31). He is a passionate art lover and dealer, with his own art and framing business in the charming town of Weesp, and recently, he has also started publishing art. Here, he perfectly combines his love for art with his entrepreneurial flair.

Whoppah explores: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

One of the most iconic design chairs is the Barcelona Chair by Mies van der Rohe. The chair was exhibited in 1929 during the World Exhibition in Barcelona and is one of the best-selling designer armchairs ever. It is amazing how a chair has not lost its popularity for more than 90 years and remains a symbol of elegant and modern design. That is why this week is an ode to architect and furniture designer Mies van der Rohe.

Whoppah explores: Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the most influential architects of the twentieth century. It's high time to find out more about this world architect!